NC Hospitals, Sheriffs Disagree Over New Mental Evaluation Process for Criminal Suspects

NORTH CAROLINA, A dispute has emerged between hospitals and law enforcement groups following the approval of new rules last year governing how criminal suspects who may need psychiatric care are handled.

State leaders approved the changes as part of broader judicial reforms aimed at keeping repeat violent offenders and individuals with serious mental illness from being released back into the community after arrest. The law restricts the use of cashless bail for certain suspects and allows judges to consider a defendant’s full criminal history — not just prior convictions — when setting bond.

A key provision of the law requires certain defendants to undergo psychiatric evaluations. This applies to individuals who were involuntarily committed within three years of being arrested for a violent crime or those judicial officials believe pose a danger to themselves or others. Under the law, these suspects must be transported to a hospital emergency department or another designated crisis facility for evaluation.

That requirement has sparked disagreement over where the evaluations should take place. Hospital leaders argue that emergency departments are not appropriate settings for evaluating potentially violent suspects, citing concerns about patient and staff safety. They have suggested that evaluations instead be conducted in jails. Sheriffs, however, oppose that approach, saying hospitals are better equipped to handle both physical and mental health assessments.

The issue is being reviewed by the state House Select Committee on Involuntary Commitment and Public Safety, which was created last year to examine North Carolina’s laws related to mental illness and the criminal justice system. The committee is expected to issue recommendations on potential legislative changes, according to co-chair Rep. Tim Reeder, a Pitt County Republican and physician.

“It’s going to require all of us to be creative and not just say, ‘It can’t be me,’” Reeder told WRAL. “Let’s problem-solve this for the protection of the public, but also make sure the alleged assailant is properly taken care of.”

Mental health issues within the criminal justice system have drawn increased attention following the recent killing of a Ravenscroft School teacher in Raleigh. That case marked at least the second high-profile murder in the state involving a suspect with a documented history of mental illness and criminal activity. Reeder’s committee is scheduled to meet again Wednesday, its first meeting since the Raleigh case.

Lawmakers initially turned their focus to mental health procedures after the August killing of Iryna Zarutska, a 23-year-old Ukrainian woman who was fatally stabbed on a Charlotte light rail train. Legislative changes stemming from that case were included in a reform package known as “Iryna’s Law.”

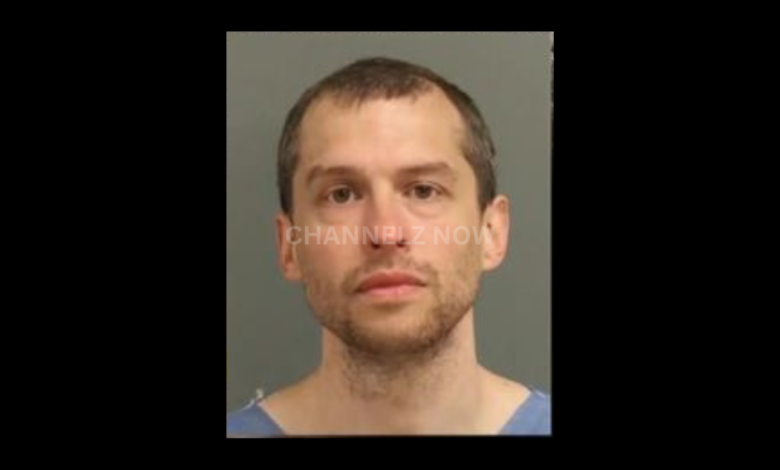

Zarutska’s accused killer, DeCarlos Brown Jr., had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and experienced hallucinations and paranoia, according to family members. More recently, Ryan Camacho — charged in the January killing of Ravenscroft teacher Zoe Welsh — was also found to have a documented history of mental illness, with prior court-ordered mental evaluations.

Rep. John Torbett, a Gaston County Republican and member of the committee, said the legislature should have addressed mental health issues in the criminal justice system years ago. He expressed hope that future reforms will allow the state to keep more dangerous individuals in mental health facilities rather than returning them to the streets.

Some provisions of Iryna’s Law related to involuntary commitment have been delayed while lawmakers consider adjustments. The mental evaluation requirement has been postponed until the end of 2026.

During the committee’s first meeting in November, hospital representatives voiced concerns about evaluating violent defendants in emergency departments, which they say are already overcrowded and ill-equipped for long-term security. They also cited a November incident in which a law enforcement officer was fatally shot during an altercation at a WakeMed emergency department in Garner.

Hospital leaders further pointed to a shortage of psychiatric beds, especially for children, which can leave patients waiting in emergency departments for extended periods. Duke University Health System officials urged lawmakers to reconsider policies that could place violent suspects near vulnerable patients.

Hospital representatives suggested using telehealth or other technology to conduct evaluations within jails. That idea was criticized by the North Carolina Sheriffs’ Association, which said jails are not designed to serve as mental health facilities and lack necessary medical resources.

Association spokesman Eddie Caldwell said hospitals are better equipped to conduct initial evaluations because they can address both physical and mental health needs. He also noted that telepsychiatry efforts in jails have produced inconsistent results, particularly when individuals are unwilling or unable to participate.

Reeder acknowledged that emergency departments are not ideal environments for criminal defendants requiring psychiatric evaluations but said the committee is still gathering feedback before proposing solutions. The panel is also expected to review outpatient commitment options, which allow individuals to receive treatment in the community under court supervision.

Reeder emphasized that the committee’s goal is to understand all perspectives before drafting legislation and cautioned against shaping policy based solely on individual cases.

“The system that we have for taking care of people with mental illness is not functioning well right now,” Reeder said. “Let’s stay focused and come up with some actionable steps that improve the system going forward.”